Ergonomic Intervention in Endoscopy: Justifying the Cost

by Marybeth Spanarkel, M.D., on January 10, 2022

Within the endoscopy environment, unique patient handling duties during colonoscopy contribute to a significantly elevated risk of job-related musculoskeletal (MSK) disorders and injury amongst endoscopy personnel.

Did you know?

- Nurses are more likely to suffer a job-related injury than any other profession in the United States

- 1/3rd of healthcare workers will be hurt on the job, with patient handling related injuries being the biggest driver

- The estimated costs associated with these injuries range from $45 to $54 billion per year

The ergonomic challenges associated with endoscopy are becoming increasingly well-recognized with both the Society of Gastroenterology Nurses and Associates (SGNA) and the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) publishing content, suggestions, and guidelines to reduce the risk to endoscopy staff.

What’s Causing the Aches and Pains? Looping.

Looping during colonoscopies is a common occurrence. Looping develops as physicians attempt to advance the colonoscope towards the cecum; however, instead of progressing forward, the scope stretches and distends the colon and “loops” upon itself. Looping most commonly occurs in the sigmoid colon, but can occur anywhere the scope encounters a barrier.

While looping can be a leading indicator of patient pain, discomfort, and failed procedures, the techniques currently employed to mitigate looping during a procedure are taking a toll on endoscopy staff. The two main techniques taught to prevent and reduce looping are manual abdominal pressure and patient repositioning. Both have inherent risks associated with them—and often the patients with the highest likelihood of looping can present as the most dangerous situations for nurses, technicians, and physicians to use these status quo techniques.

I have spent greater than 25 years performing a large volume of colonoscopies, and I believe the most overlooked risk to musculoskeletal injuries (for both physicians and ancillary staff) is the phenomenon of “looping” and the forces required to mitigate this problem.

The increased number of females entering the field of GI demand more attention to the ergonomic risks of high-volume procedure performance.

Manual Abdominal Pressure

Manual pressure is performed in about 60-70% of all colonoscopy procedures. This technique is often used to decrease the mobility of the colon—splinting it and giving the scope a solid surface to use as leverage, versus stretching and distending the colon. Manual pressure can also be used to help physicians navigate the more difficult gastrointestinal anatomy such as the splenic and hepatic flexures.

The main drivers of ergonomic risk associated with manual abdominal pressure are:

- Awkward posture

- High force

- And a high frequency or long duration of use during a difficult colonoscopy.

Oftentimes during a challenging colonoscopy, endoscopy staff look as if they are practicing wrestling moves on a patient to advance the scope. Nurses and technicians are often required to lean over the patient, bend down at an awkward angle, or hold pressure for an extended period—increasing the risk of MSK injury associated with the neck, arms, and wrists.

As a high volume endoscopist, I have seen difficult colonoscopies requiring hands, arms, forearms, and elbows applied with “full force” indiscriminately into a patient’s abdomen. We must attend to this risk, not only for the patient and the colonoscopist, but also for the invaluable staff required to maintain excellence in the endoscopy suite. Their importance CANNOT be underestimated or diminished!

Due to manual pressure:

- 50% of endoscopy staff will suffer from one or more musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs)

- 28% of staff will have to miss work due to an injury

- 41% of endoscopy staff use analgesics for upper extremity pain

- 14% of endoscopy staff have undergone corrective surgery due to injuries sustained while on the job

For those of you that have difficulty understanding the concept of ”looping,” this is an excellent video demonstrating this frequent problem in colonoscopy.

Injuries to endoscopy staff may, indeed, be the main reason for high turnover in units, and this turnover itself a very costly endeavor. The Covid pandemic has highlighted not only the unmeasurable importance of our nursing staff, but also the appropriate unwillingness of the staff to be put in risky positions!

Patient Repositioning

When manual abdominal pressure fails to advance the scope towards the cecum, patient repositioning is the next go-to technique. Repositioning is performed in about 20-40% of all colonoscopy procedures. Under sedation, moving a patient is incredibly challenging. Adding to that, approximately 30-40% of the American population is now considered medically obese. Patients with a higher BMI pose a particularly dangerous risk for staff if repositioning is required during colonoscopy.

Are There Risks to the Patient?

Unfortunately, yes. ColoWrap conducted a survey during the 2021 SGNA Annual Course where 26% of respondents had observed complications due to abdominal pressure and repositioning. The most common complications observed were:

- Post-procedural abdominal pain and bloating

- Bruising

- Splenic ruptures (VERY rare, but incredibly risky for the patient)

The serious complications of colonoscopy are well known—perforation, bleeding, and the very rare splenic injury. But colonoscopists who perform large volume cases and do a fair share of “difficult“ colonoscopies, may be unaware of, or under-report, the complaints of post-procedure abdominal pain and/or bruising.

I suspect that both the serious complications as well as the less serious (but more common) pain/bruising are BOTH related to the phenomenon of applying pressure and force to mitigate a difficult redundant colon.

Learn More About Patient Injury Due to Pressure:

- Abdominal Wall Hematoma Resulting From Abdominal Pressure Applied During Colonoscopy

- Mesenteric Tear Can Be Caused by Abdominal Counter-Pressure Applied During Colonoscopy

What’s the Solution?

To address looping during colonoscopy, manual abdominal pressure continues to be the current reactive technique. Unfortunately, as ergonomic issues and studies around potential ergonomic challenges continue to be researched, it is beginning to look like the status quo will always be a risky endeavor.

In a study conducted by ColoWrap, using xSensor pressure mapping gloves and an experienced Endoscopy Technician, the Company found that on average GI staff were routinely applying 50 to 115 pounds of force for ten minutes or more per colonoscopy. This is far beyond the established safe patient handling limits, which indicate a safe level of push force for males is 33 pounds and 22 pounds for females. Pressure, even at these “safe” levels, should never be applied for more than five minutes per day.

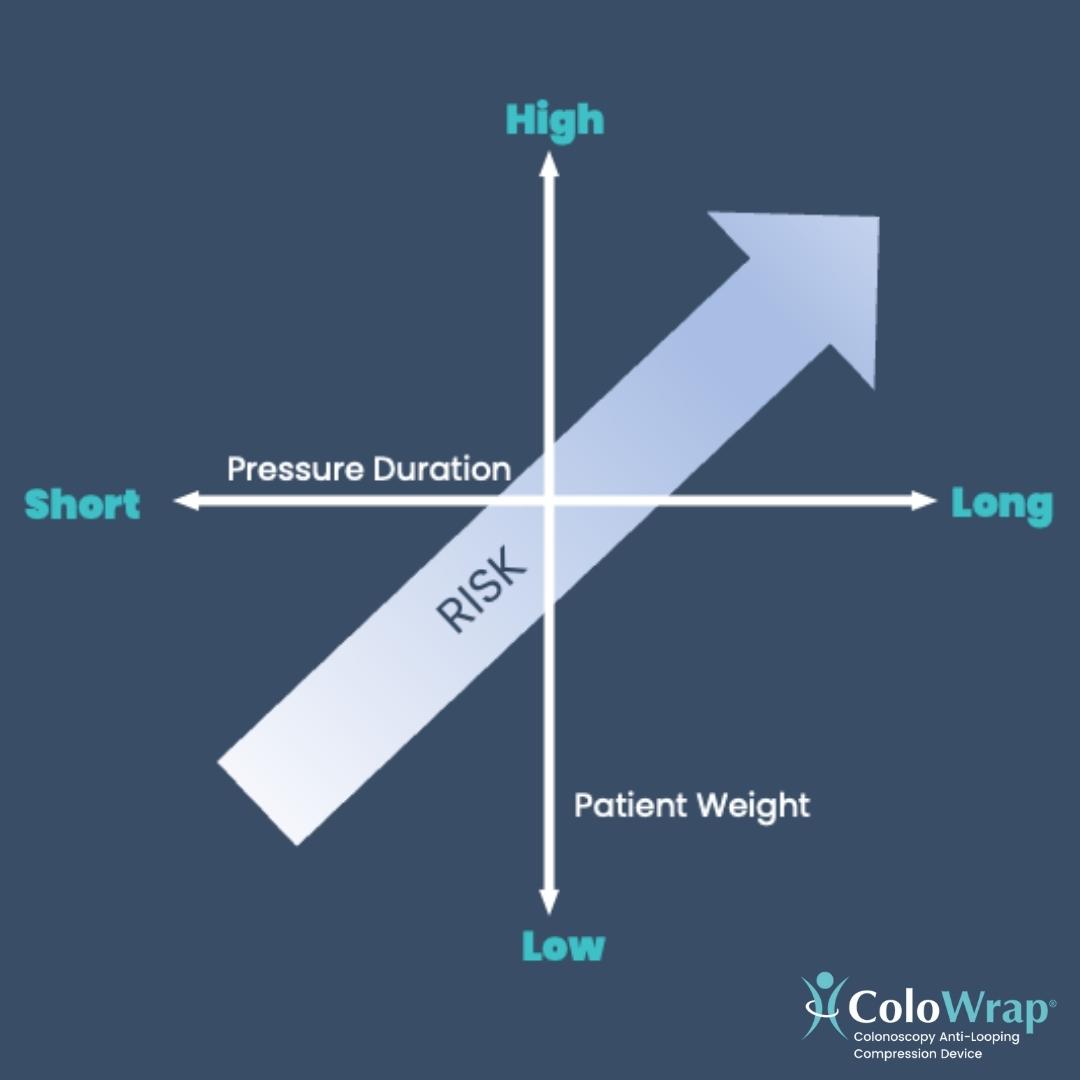

While the patient is clearly at risk due to exceeding pressure guidelines, the endoscopy staff applying pressure is far exceeding ergonomic standards as well—therefore, continually putting themselves at risk for injury. This risk of injury increases depending on the patient's body size and weight. As body size and weight increase, the amount of force required increases—leaving endoscopy staff at a higher risk of injury.

The Key to Success — Risk Mitigation

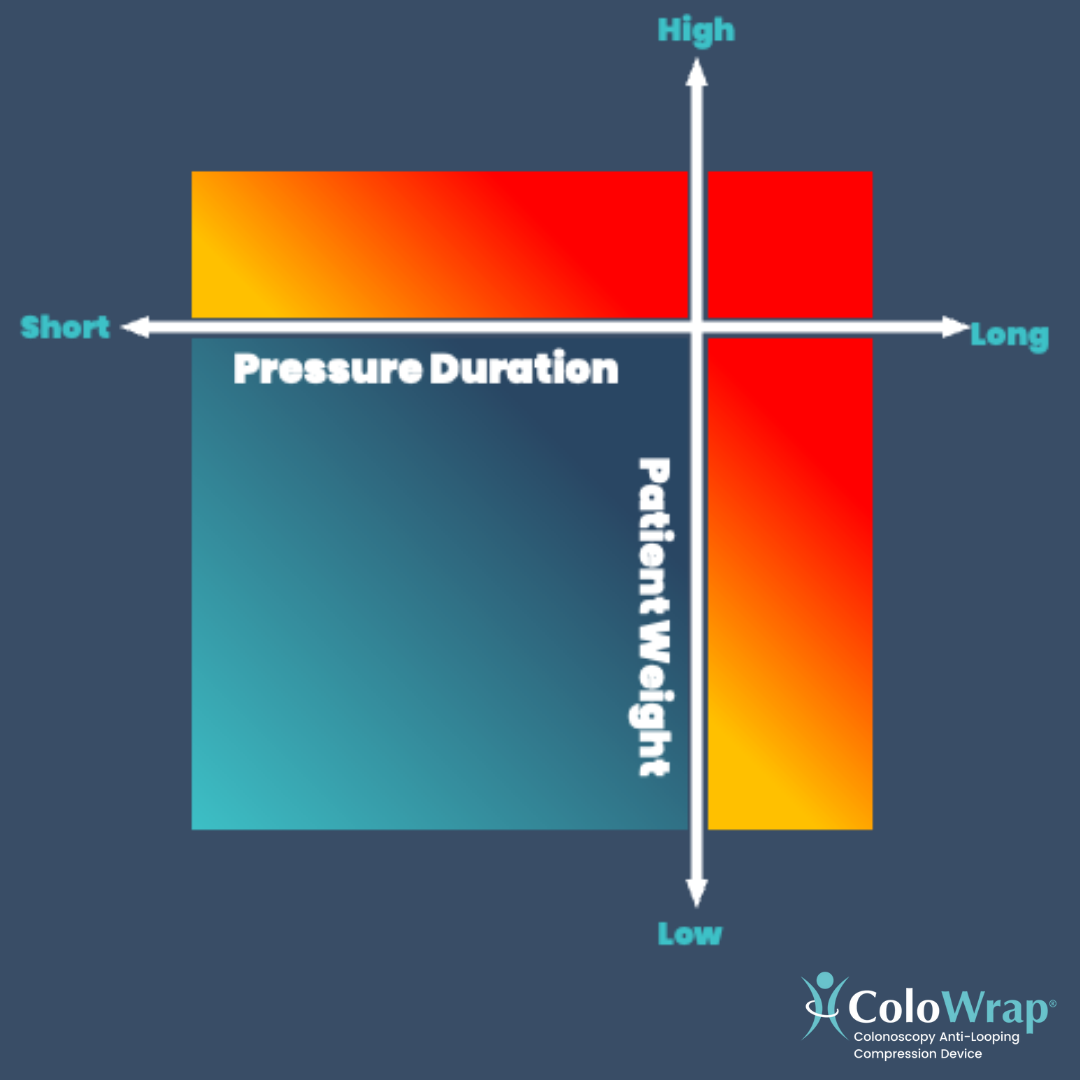

The key to reducing the ergonomic risks, and patient risk, driven by force and duration of manual pressure is to understand the continuum of what makes a difficult colonoscopy risky.

While the status quo method of applying manual pressure works in the right situation, as you approach the above “Red Zone,” it is important to find alternatives to delivering pressure with a keen eye on endoscopy staff and patient safety.

Patients in the “Blue Zone” can safely receive pressure, and are typically:

- Younger

- Fitter

- Have abdominal tone

- A candidate for adult colonoscope

Patients in the “Red Zone” cannot safely receive pressure, and are typically:

- Larger—with a BMI greater than 30

- Have had a prior incomplete or challenging colonoscopy

- Have an abdominal hernia

- Have had prior abdominal surgery

- Are having an unsedated colonoscopy

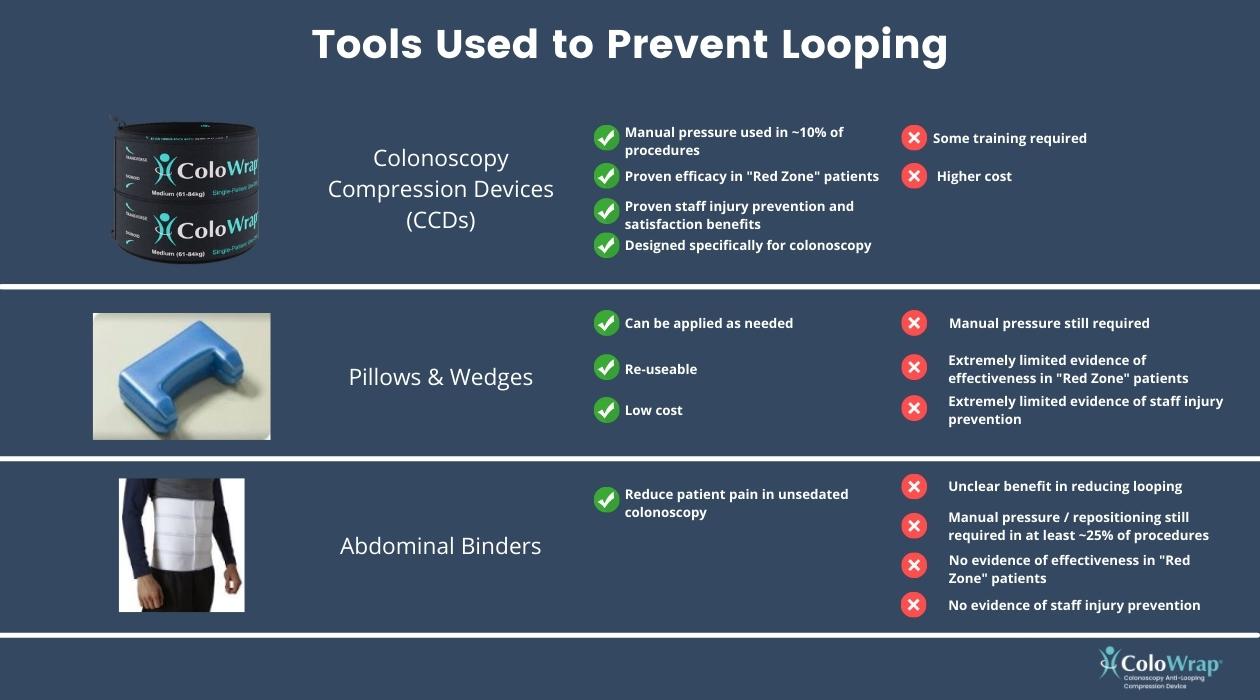

When performing a colonoscopy on a “Red Zone” patient, it is critical that all ergonomic and patient risks assumed from applying manual pressure and/or repositioning be mitigated. As it stands, there are three tools that may be effective in reducing the potential for loop creation—Pillows/wedges, abdominal binders, and colonoscopy compression devices.

Are the Costs of Colonoscopy Compression Devices Justified?

Traditionally, return-on-investment (ROI) calculations within healthcare narrowly assess benefits and often fail to grasp the true economic value of new products, techniques, and interventions. Regarding ergonomic intervention within endoscopy, a simple ROI model would analyze the cost of a device versus projected savings associated with injury costs and workman’s compensation due to manual pressure driven injury amongst staff.

However, when using a Systems Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety (SEIPS) analysis to quantify such an ergonomic intervention within endoscopy, the full value becomes more readily understood. The International Ergonomics Association (IEA) recently published a synopsis of such an intervention: “Using SEIPS for Cost Justification of An Ergonomic Intervention in Endoscopy,” which is extracted from a soon-to-be-published book, “Ergonomics for Endoscopy: Optimal Preparation, Performance, and Recovery,” edited by Dr. Amandeep Shergill, pulished by Slack Incorporated.

The Site Study

ColoWrap colonoscopy compression devices (CCDs) were used at a community hospital that performs around 2,500 colonoscopies per year. The endoscopy unit had suffered an injury in the year prior year which was attributed to the need for manual pressure and patient repositioning during colonoscopy. The total cost of this injury amounted to $106,000—due to lost time, staffing, surgery, and related medical expenses. The endoscopy unit consists of eight registered nurses (RNs) and three endoscopy technicians.

The ROI

A simple cost justification model looking at the ergonomic intervention of a colonoscopy compression device would narrowly focus on:

- The reduction of manual pressure

- The reduction of patient repositioning

- The reduction of endoscopy staff musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs)

- The reduction of injury costs and workman’s compensation

The report takes the analysis much further using SEIPS and the far-reaching consequences of such an intervention begin to become obvious. The multitude of variables identified as an outcome of colonoscopy compression device-driven ergonomic intervention are as follows:

- Reduced looping during colonoscopy

- Reduced push force, torquing of the scope

- Reduced Endoscopists MSDs

- Reduced equipment wear and tear

- Increased procedural volume

- Increased revenue

- Decreased scope repair costs

- Reduced push force, torquing of the scope

- Reduction of manual pressure and patient repositioning

- Reduced endoscopy staff MSDs

- Reduced injury costs / workman’s compensation

- Reduced call outs and absences

- Reduced presenteeism

- Reduced staff turnover

- Reduced patient complications

- Increased patient satisfaction

- Reduced post-procedure ED visits

- Reduced endoscopy staff MSDs

- Decreased difficulty in reaching cecum

- Reduced number of incomplete colonoscopies

- Improvement of colonoscopy volume, increasing revenue

- Improved productivity, reducing staff overtime hours

- Improved patient satisfaction

- Reduced number of prolonged procedures

- Improved productivity, reducing staff overtime hours

- Reduced frequency/duration of patient pain and sedation requirements

- Improved patient satisfaction

- Reduced post-procedure ED visits

- Reduced number of incomplete colonoscopies

- Reduced procedure time

When taking the holistic information derived from the SEIPS model, using a colonoscopy compression device as a tool for ergonomic intervention within the endoscopy unit proves to be highly valuable. The analysis concludes that in the hospital setting, a CCD can achieve a cost benefit ratio of 1:4.35, or in other words, the ROI on such a device is 435%. In the hospital setting described above, it was estimated that the hospital could achieve a $588,924.75 financial benefit due to ergonomic intervention via a colonoscopy compression device. In summary, there is an incredible opportunity for cost savings and a positive return-on-investment using such a device—while also ensuring the safety of patients, endoscopy staff, and endoscopists.

The revenue per colonoscopy is only one variable in the economic success story of any unit. Physicians and unit managers need to strongly consider the overall costs of nursing turnover, workman’s compensation, delayed schedules (due to difficult cases), and patient reviews. In addition, if one provider is injured (I was one of five busy endoscopists. After a sudden injury resulting in surgery, the overall cases and thus revenue was immediately reduced 20%!) One out of every 5 GI physicians suffers a MSD injury!

Doctors and ancillary staff in hospital-based endoscopy suites provide a large revenue stream to the hospital. It is imperative that these institutions protect these individuals from injury with proper ergonomic environments. Perhaps the overall revenue stream for the hospitals should be appropriately reduced by ergonomic investment in the endoscopy unit?

Want to learn more?

Check out the full analysis here: Using SEIPS for Cost Justification of An Ergonomic Intervention in Endoscopy

Want to get started with ColoWrap? Contact one of our experts today.

Posted by Marybeth Spanarkel, M.D.

Marybeth Spanarkel MD was a clinical gastroenterologist at the Duke Regional Hospital in Durham NC for over 28 years. Post retirement, she has been a Senior Medical Advisor for ColoWrap and a passionate advocate for ergonomic advances in colonoscopy. A graduate of Duke Medical School, she completed advanced training at the University of Pennsylvania, Johns Hopkins, and the NIH prior to her clinical career. She is the mother of four children and enjoys family, traveling, and sports (especially the Blue Devils!)